MoPar

torsion bars and crossmembers replace conventional Olds components. |

Controlling two engines is a

task. Hurst handled it by using two Moon hydraulic throttle controls together with a pair

of accelerator pedals that are placed side by side. This makes it possible to clear each

engine separately and listen to them before takeoff, and also to control the engines

together during the actual driving. Dave Landrith is thinking in terms of some more

sophisticated control systems, such as an electrical speed synchronizing system that would

automatically control the throttles of each engine and prevent either one of the engines

from racing away with the tires broken loose.

Both transmissions seem to

shift fairly close to each other, and are controlled manually. Throttle vacuum response

controls have been omitted. Control of both transmissions so that they work absolutely in

unison can be effected by using a single common governor and valve body. This has not been

needed to date.

A switch within easy reach of

the driver controls the stator pitch in both torque converters. Starts are made with a

torque converter at a high angle, giving maximum torque mulitplication. Thus it is

possible to break the tires loose quickly and avoid breaking the axle stubs. With the

vanes at the high angle, the engine receives the benefit of maximum stall speed. As soon

as the car gets out of the hole, the switch is flipped and the torque converters shift

back to the low-angle pitch and stay there for the remainder of the run.

|

|

Left: Injection inlets face to

the rear on the trunk-mounted engine to protect the driver and to avoid the low pressure

build-up inside the car. Right: Sharp Engineering manifolds with GMC-Hilborn setups are

used fore and aft. |

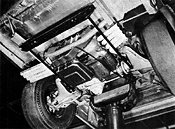

Retaining the Oldsmobile

suspension and driveline offers the benefits of independent four-wheel suspension and

minimizes load transfers from side-to-side. There is also a safety advantage, since each

wheel is mounted on a full floating hub. If a stub does break, the car can still continue

to roll.

There is a scarcity of gear

ratios for the unique Toronado differential. One solution Dave Landrith and Jack Watson

proposed was to make up different sprockets for the chain drive between the engine and the

transmission. To carry all this power to the ground, the Hurst boys picked a set of M

& H Racemaster 8.50-15 slicks with 260 compound. Tire pressures are kept at 40

psi in the rear and 35 up front, indicative of the load transfer that is to take place on

acceleration.

Kelsey Hayes disc brakes are

fitted at the front (is it a preview of things to come?), while the rear brakes are stock.

A bar allocates the pedal pressure to the two master cylinders in the proper ratio to

tailor the front-to-rear brake action. Making room for the disc brakes entailed a

different offset at the wheels.

Hairy

Hauler carries car, slicks, engine goodies and lots of fuel. |

The Hurst Hairy Olds is

completed in a true Hurst tradition, perfect down to the last detail. The car is topped by

an impeccable gold and black paint job. It is carried by a vehicle that is no less

imposing than the car itself. Appropriately dubbed the "Hairy Hauler", the unit

incorporates just about every modern feature that a drag racer would want in his own

truck, including ramps, a power winch, storage chests and a rack for the slicks: a Hurst

extravaganza!